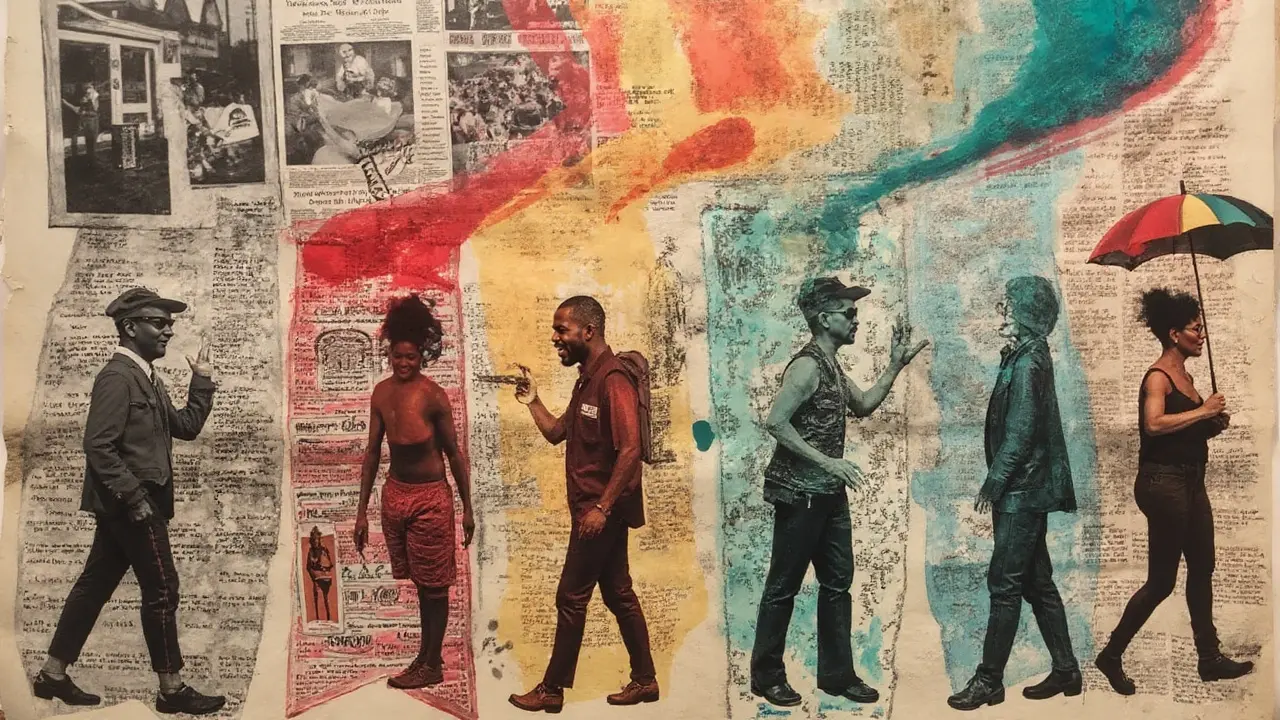

Queer history keeps editing out the people who paid the bill. Sex workers-especially trans women of color-were not background characters at Stonewall or Compton’s Cafeteria. They organized, fought back against police raids, and built the mutual aid networks that kept people alive when services looked the other way. If we’re honest about what kept the community standing, sex work isn’t a footnote-it’s the spine.

First, clarity. Sex work means consensual exchange of sexual services or erotic labor for money or goods. Trafficking means coercion, force, or fraud. Mixing these up doesn’t protect people; it makes policy sloppy and pushes consensual workers into the shadows where services and safety tools get stripped away.

Why this matters right now: criminalization falls hardest on those already shut out-trans people, migrants, Black and brown communities, people with records. For many, sex work is what pays rent when bias blocks other jobs. It’s also how safer sex messaging and HIV prevention spread peer‑to‑peer in the 80s and 90s when official channels failed. That outreach culture never left; it’s how bad laws get flagged, how unsafe actors get warned about, and how people get to tomorrow.

The evidence is not fuzzy. A 2015 series in The Lancet modeled that decriminalization could reduce HIV infections among sex workers by roughly one‑third to nearly one‑half over a decade, driven by less violence and better access to health care. New Zealand’s 2003 law decriminalizing sex work, reviewed by its government in 2008 and later studies, found no rise in trafficking, improved ability to refuse clients, and better relations with police and clinics. In the U.S., economists Cunningham and Shah found that the rollout of Craigslist’s erotic services years ago correlated with a 17% drop in female homicide rates-safer screening saves lives. During Rhode Island’s 2003-2009 period when indoor sex work was de facto decriminalized, reported rapes fell about 31% and female gonorrhea dropped about 39%.

Policies that sound protective can backfire. The 2018 FOSTA‑SESTA law pushed people off safer online platforms and back into riskier street‑based or third‑party controlled settings. Community research by Hacking//Hustling (2020-2021) documented increased violence, worse financial instability, and fewer options to screen clients. “End demand” or Nordic model laws, which criminalize buyers and third parties while leaving selling technically legal, still drive the market underground; multiple evaluations in France and Canada show more rushed negotiations and higher violence risk because everyone is hiding.

If you’re a policymaker or advocate, start with what reduces harm: decriminalization, not legalization schemes that add heavy licensing barriers; end the use of condoms as evidence; expunge records for prostitution‑related offenses; fund peer‑led drop‑in centers; and fix platform liability rules so adults can use online tools to screen and share safety info. Back housing, immigration support, and identity document access-these reduce the reasons people get trapped in unsafe situations far more than stings ever will.

If you’re an ally wondering what to do today, put money and power where they help most. Support organizations like SWOP‑USA, Red Canary Song, Decriminalize Sex Work, and the New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective. Ask your local LGBTQ center if sex workers have seats on boards and stipends for their labor. When decrim bills show up in your city or state, read the text, attend the hearing, and submit a short statement that cites the New Zealand outcomes and The Lancet findings-data talks when stigma is loud.

For people doing the work, safety planning is not a luxury. Build a check‑in routine with a trusted person, use a separate work device or profile, turn on two‑factor authentication, and keep notes on incidents in a secure place. Learn your local laws and your rights during police encounters. If you’re willing, connect with a peer network to share bad‑date info and community resources. None of this replaces good policy, but it can blunt the harm while we push for it.

- Roots and Uprisings

- Definitions and Realities

- Evidence for Decriminalization

- Harm and Policy Myths

- Practical Steps and Resources

Roots and Uprisings

The first sparks of modern queer resistance weren’t boardroom speeches-they were street fights against routine police harassment. Trans women of color, street queens, and hustlers were on the front line because they were the ones getting stopped, searched, and booked the most. That pressure cooked anger into action, and those actions set the template for everything we now call LGBTQ rights.

Compton’s Cafeteria, San Francisco, August 1966: police tried another late-night sweep of the Tenderloin. Someone threw coffee at an officer, a plate shattered a window, and the room erupted. This wasn’t random. Vanguard, a queer youth group backed by Glide Memorial Church, had already picketed Compton’s in July for ejecting trans patrons. Historian Susan Stryker’s documentary “Screaming Queens” tracks how that clash became one of the first known transgender-led uprisings in the U.S., pushing the neighborhood toward clinic access and drop-in services instead of just raids.

Stonewall, New York City, June 28, 1969: a routine raid met unusual resistance at the Stonewall Inn. The crowd swelled over several nights. Street-involved queer and trans people-many doing survival economies on the piers and in Times Square-were not bystanders; they ran bail, scouted police movements, and linked up with early groups like the Gay Liberation Front and Gay Activists Alliance. Names you’ll recognize-Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera-weren’t just icons; they were relentless organizers who kept showing up when others faded.

By 1970, Johnson and Rivera launched Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). STAR wasn’t a think tank; it was a crash pad, a hot meal, clothing, and political education for street-involved youth and sex workers. It’s a blueprint we still copy: secure a roof, cover basics, build power, and show up at city hearings even when the room looks hostile.

Across the Atlantic, June 1975, more than a hundred sex workers occupied Saint-Nizier Church in Lyon, France, for eight days. They were protesting unsolved murders, police crackdowns, and fines that made safety impossible. The sit-in spread to other cities and put labor language-rights, not pity-at the center of debate. European reporters covered it daily, and the tactic shaped later organizing from Paris to Berlin.

In San Francisco, Margo St. James founded COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics) in 1973. COYOTE held speak-outs, ran legal hotlines, and met with city officials about policing and health. The line from there to today’s clinics and worker-led unions is pretty direct: talk openly, gather data, and push the press to print the record.

| Year | Event | Location | Trigger | Who Led | Notable Outcome | Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Compton’s Cafeteria Riot | San Francisco (Tenderloin) | Police harassment and ejections of trans patrons | Trans women, street queens, Vanguard youth | Early transgender-led uprising; jump-started community services | Dozens+ |

| 1969 | Stonewall Uprising | New York City (Greenwich Village) | Police raid on the Stonewall Inn | Street-involved queer and trans people; allies | Sustained protests; birth of annual Pride marches | 1,000+ over several nights |

| 1970 | STAR founded | New York City | Need for housing and safety for street-involved youth | Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson | STAR House model: shelter + organizing | ~20 residents at peak |

| 1975 | Saint-Nizier Church Occupation | Lyon, France | Violence, fines, and police crackdowns | Local sex worker collectives | Shifted debate toward labor rights across Europe | 100+ for 8 days |

These weren’t isolated flares. They built a repeatable playbook: stabilize people first, make police behavior visible, talk to press with simple facts, and bring demands that anyone can understand. When later fights over HIV funding, housing, or IDs came up, that playbook delivered wins because the base was organized, not theoretical.

If you’re building campaigns today, pull three lessons from these roots: center people most targeted by law enforcement, build material support (beds, food, legal help) before you chase policy, and document everything so the next group doesn’t start from zero. That’s how uprisings turn into durable change, including the push for sex work decriminalization.

- Primary sources to read or watch: “Screaming Queens” (2005), Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries zines and interviews, and the Christopher Street Liberation Day march flyers from 1970 (archived at the New York Public Library).

- Practical step: when you cite this history in testimony or op-eds, include dates, names, and the specific demand tied to each action. It keeps debates grounded and hard to dismiss.

Definitions and Realities

Start with the basics. Sex work is a consensual exchange of sexual services or erotic labor for money, goods, or housing. Trafficking is different: it involves force, fraud, or coercion. Under U.S. law (the Trafficking Victims Protection Act) and the U.N. Palermo Protocol, any commercial sexual activity involving a person under 18 is trafficking, even if no coercion is proven. Mixing these terms blurs who needs what kind of support and can lead to laws that miss the mark.

Sex work is an umbrella term. It covers more than full-service work. People earn through different kinds of erotic labor, sometimes overlapping, often part-time or seasonal. That matters for policy and safety because risks, control, and bargaining power vary across settings.

- Full-service (in-person sexual services)

- Stripping and club work

- Camming and clip creation

- Phone and text-based services

- Pro-dom/me and fetish services

- Porn performance and content creation

“Third parties” is a broad category too. It can mean exploitative managers, but it also includes drivers, translators, security, web moderators, and site owners. Good laws draw a line between exploitation and legitimate support roles.

Now the legal models. They sound similar but work very differently on the ground.

- Criminalization: Buying and selling are illegal. This is the default in most of the U.S. (with a narrow exception for licensed brothels in some rural Nevada counties-Las Vegas and Reno are not included).

- Partial criminalization: Some activities (like “brothel-keeping,” “solicitation,” or “living off earnings”) stay illegal, which still keeps people hiding and negotiating in rushed conditions.

- “End-demand”/Nordic model: Selling is technically legal, but buying and many third-party roles are criminalized. Multiple evaluations in France (2018-2020) and Canada (post-2014 PCEPA) report more hurried negotiations and higher exposure to violence because everyone is avoiding police.

- Legalization (licensing): Sex work is legal but only within strict licensing or zoning. In practice, many workers end up outside the system due to fees, background checks, or ID barriers, so a two-tier market persists.

- Decriminalization: All consensual adult sex work is removed from criminal law, with standard labor, health, and safety rules applying. New Zealand’s Prostitution Reform Act (2003) is the clearest example; government reviews found improved ability to refuse clients and better access to clinics and police without evidence of increased trafficking.

Global context matters. The International Labour Organization estimates 27.6 million people in forced labor worldwide in 2021, including about 6.3 million in forced commercial sexual exploitation. Those numbers speak to trafficking and coercion, which require strong worker-centered responses. At the same time, the World Health Organization (2012, 2014) and Amnesty International (2016) have called for sex work decriminalization to reduce violence and improve health access for consenting adults.

For queer communities, the realities are shaped by discrimination. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey reported a 15% unemployment rate among respondents-about three times the national rate that year-and high poverty. When housing and jobs are blocked by bias or mismatched IDs, the informal economy, including sex work, becomes a survival strategy. That’s not theory; it’s the reason peer-led mutual aid networks show up where formal services fall short.

Policing practices shape safety too. Using condoms as evidence of prostitution has been common in some places, despite public health pushback; California’s SB 233 (2019) barred that and added protections for reporting crimes. New York repealed its “Walking While Trans” loitering law in 2021 after years of profiling complaints. These are nuts-and-bolts changes that move people from hiding to help.

The internet changed the landscape, then laws changed the internet. In 2018, Congress passed FOSTA-SESTA, which carved a hole in Section 230 for content related to prostitution and trafficking. Platforms shut down personals and moderation tools; Backpage had already been seized that April. Researchers and community surveys (including Hacking//Hustling, 2020-2021) documented more risky in-person dates, fewer options to screen, and higher financial instability after those shutdowns.

Two more realities that get lost in debates:

- Consent is dynamic. A worker can agree to services, then change their mind or set new limits. Decriminalized settings make it easier to enforce “no” because workers can leave, call backup, or seek help without fear of arrest.

- Safety tools are simple but powerful. Screening, blacklists/“bad date” lists, secure messaging, and buddy check-ins are basic harm reduction. These depend on open communication channels, not shadow markets.

Finally, language is not just politics. Calling all sex work “trafficking” misdirects resources away from forced-labor investigations and hurts adults who are choosing the work but need safer conditions, fair pay, housing, and health care. Clear terms let us build policies that actually reduce harm-whether someone needs an exit ramp, better working conditions, or both.

Evidence for Decriminalization

The case for sex work decriminalization is built on hard numbers, not vibes. When criminal penalties drop, violence and infections fall, and access to health care and police protection goes up. Multiple studies across countries point in the same direction.

Start with HIV. The Lancet’s 2015 modeling (Shannon et al.) estimated that removing criminal penalties could cut new HIV infections among sex workers by roughly 33-46% over a decade. The mechanism wasn’t magic-it was less violence, better access to condoms and clinics, and more power to refuse risky clients.

New Zealand is the real‑world test. After the Prostitution Reform Act (2003) decriminalized sex work, the government’s 2008 review and follow‑up research found no surge in the number of sex workers, improved ability to refuse clients, better workplace safety practices, and no evidence of increased trafficking. Relationships with police and health services improved because people could report abuse and actually be heard.

In the U.S., two natural experiments tell you what safer conditions do. During Rhode Island’s 2003-2009 period when indoor sex work was effectively decriminalized, economists Scott Cunningham and Manisha Shah found reported rapes fell about 31% and female gonorrhea dropped about 39%. Separately, when Craigslist’s “erotic services” section rolled out city by city, a later study by Cunningham, DeAngelo, and Tripp linked it to ~17% fewer female homicides-screening clients online and moving indoors saved lives.

Policies that keep selling technically legal but criminalize clients or third parties (the so‑called Nordic model) don’t match those outcomes. France adopted client criminalization in 2016; Médecins du Monde’s 2018 evaluation reported more violence against sex workers and more rushed negotiations because everyone had to hide. Canada’s 2014 law (PCEPA) shows similar patterns in community studies: more fear of police contact and worse screening, which increases risk. That’s why WHO and UNAIDS recommend decriminalization as part of HIV prevention, not end‑demand models.

| Study / Location | Policy shift | Key outcomes | Source / Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Lancet (global modeling) | Decriminalization (modeled) | 33-46% fewer new HIV infections among sex workers over 10 years | Shannon et al., 2015 |

| New Zealand | Full decriminalization (PRA 2003) | No increase in sex worker numbers; improved right to refuse clients; better access to police and health services; no evidence of increased trafficking | Prostitution Law Review Committee, 2008; Abel et al., 2009-2010 |

| Rhode Island, USA | De facto decriminalized indoor work (2003-2009) | Reported rapes −31%; female gonorrhea −39% | Cunningham & Shah, 2014-2016 |

| Craigslist rollout, USA | Online screening/information channel | ~17% drop in female homicide rates in treated cities | Cunningham, DeAngelo & Tripp, 2019 |

| France | Client criminalization (2016) | Increased violence and risk; more rushed negotiations; worse health access | Médecins du Monde evaluation, 2018 |

Why do these results repeat? Decriminalization changes the daily calculus:

- People can call the police without risking arrest, which deters predators.

- Condoms stop being "evidence," so safer sex goes up, not down.

- Workers can screen, negotiate, and refuse-basic levers that cut violence.

- Indoor work and third‑party support (drivers, security, reception) become safer options.

- Clinics and outreach can engage openly, so testing and treatment stick.

If you’re sizing up a new bill or program, look for these measurement basics:

- Track police‑reported violence, emergency room assaults, and community bad‑date logs before and after policy changes.

- Use STI/HIV incidence, not just positivity rates, and watch condom distribution/use trends.

- Check whether reporting improves (more reports can mean more trust, not more crime).

- Ask whether the law lets adults use platforms to screen clients; when those vanish, risk climbs.

- Include sex worker‑led orgs in designing the evaluation-survivor and worker input catches blind spots.

The bottom line from the data: when the law stops punishing consensual adult sex work, harm drops fast and stays lower. That’s not a theory problem-it’s a policy choice.

Harm and Policy Myths

Good policy starts with facts, not vibes. A lot of well-meaning laws end up making people less safe. Here are the common claims you’ll hear, and what the evidence actually shows.

Myth: Cracking down on sex work reduces trafficking.

What the data shows: Broad crackdowns mostly net consenting adults, not traffickers. When New York City shifted away from prosecuting prostitution in 2021, the Manhattan DA vacated hundreds of old cases and said the old approach didn’t improve safety. After the U.S. passed FOSTA-SESTA in 2018, researchers and community surveys (like Hacking//Hustling’s 2020 report) documented lost income, fewer screening tools, and more exposure to violence. Ads didn’t disappear; they scattered to harder-to-moderate sites, which helps bad actors hide.

Myth: The “Nordic model” (punishing buyers, not sellers) keeps workers safe.

What the data shows: France adopted this model in 2016. Médecins du Monde and community groups reported more rushed negotiations, more hidden meetings, and higher risks because everyone is avoiding police. Canada’s 2014 version (PCEPA) produced similar problems-federal reviews in 2022 heard consistent testimony about continued stigma and barriers to reporting violence. Sweden’s own evaluations show displacement (work moving indoors or online), not elimination.

Myth: Legalization with heavy licensing is the safest option.

What the data shows: Systems that require expensive licenses, registration, or employer sponsorship create a two-tier market. People who can’t clear those hurdles still work, but with less protection. New Zealand took a different route in 2003: decriminalization with basic health and safety standards. The government’s 2008 review found workers were more able to refuse clients, access clinics, and report violence, with no evidence of an increase in trafficking.

Myth: Shutting down online platforms protects people.

What the data shows: Moving from regulated online spaces to the street or opaque apps makes screening harder. When Craigslist’s “erotic services” section expanded, economists Cunningham and Shah found a 17% drop in female homicide rates-better screening saved lives. Rhode Island’s 2003-2009 window when indoor sex work was effectively decriminalized saw reported rapes fall about 31% and female gonorrhea drop about 39%. Taking away safer tools reverses those gains.

Myth: Using condoms as evidence helps catch abusers.

What the data shows: It stops people from carrying condoms. Human Rights Watch documented this in multiple U.S. cities. Policymakers have started to fix it: New York City ended the practice in 2014, and California’s SB 233 (2019) bans condoms as evidence in prostitution cases and protects people who report violence or trafficking.

Myth: Vice raids and “rescue” stings are low-risk.

What the data shows: They can be deadly. In 2017, Yang Song died during an NYPD vice raid in Queens. Raids often push migrants and trans workers further from services and make everyone less likely to call 911. Most arrests are for low-level charges, not trafficking kingpins.

The pattern is the same: criminalization and “end demand” push the market into riskier corners, cut off safety info, and strain trust with health and police services. The evidence favors sex work decriminalization paired with labor rights and harm reduction.

If you’re weighing a bill, pressure-test it with quick checks:

- Does it punish buyers, third parties, or roommates in ways that make screening and safety harder?

- Does it let adults share workspace, drivers, or security without risking “brothel-keeping” or “pimping” charges?

- Does it block online ads or messaging that workers use to screen clients and warn each other?

- Does it bar condoms, lube, or health records from being used as evidence?

- Does it add Good Samaritan protections so people can report violence, overdose, or trafficking without being arrested?

- Does it fund peer-led outreach, housing, and immigration support-the things that actually reduce exploitation?

One more clarity point that matters for results: sex work is consensual. Trafficking involves force, fraud, or coercion. Policies that blur this line make services harder to reach and let real traffickers blend in. Keeping the line sharp is how you protect people and catch abusers.

Practical Steps and Resources

This is where talk becomes action. Below are concrete moves for policymakers, service providers, allies, platforms, and people doing the work. I’m keeping it short, specific, and linked to what’s proven to reduce harm.

For Policymakers

- Back sex work decriminalization. A 2015 series in The Lancet projected that removing criminal penalties could cut new HIV infections among sex workers by roughly one-third to almost half over 10 years, mainly by reducing violence and improving access to health care.

- Use New Zealand as your baseline. Since the 2003 Prostitution Reform Act, government reviews found workers had more power to refuse clients and report violence, with no evidence of a trafficking surge. Police and clinics reported better cooperation.

- Stop using condoms as evidence. New York State banned this in 2018. California’s SB 233 (2019) also bans condom evidence and gives limited immunity from arrest for people reporting certain violent crimes.

- Clean up loitering laws. New York repealed its “Walking While Trans” loitering statute in 2021. Repeal and expunge similar laws that enable profiling.

- Fund peer-led support. Pay for drop-in centers, mobile outreach, housing, ID help, and legal aid run by people with lived experience. Peer programs consistently show higher uptake of services.

- Fix platform liability. FOSTA-SESTA (2018) narrowed Section 230 and helped push workers off safer online tools; Craigslist shut Personal ads the same week. Support federal/state reforms that let adults use screening and safety features without platforms fearing criminal liability.

- Expunge and vacate records. Create easy pathways to clear prostitution-related records. Cut fines and fees that trap people in court debt.

- Data and dignity. Require police departments to track and publish use-of-force, stop data, and outcomes of stings. Fund independent harm evaluations, not just arrest counts.

For Service Providers (Clinics, Shelters, Legal, Crisis Teams)

- Make access simple. Drop ID barriers, offer walk-in hours, and keep a clear “no police in waiting room” policy unless there’s an immediate safety threat.

- Confidentiality first. Train staff on privacy, chosen names, and pronouns. Do not collect more data than you need. Know your state’s mandatory reporting rules and explain them up front.

- HIV prevention that works. PEP is effective if started within 72 hours of exposure; PrEP reduces sexual HIV risk by about 99% when taken as prescribed (CDC). Stock PEP or set rapid referral pathways. Offer PrEP, STI testing every 3-6 months for higher risk, and vaccines (Hep A, Hep B, HPV per eligibility).

- Don’t police safety tools. Never confiscate condoms or lube. Offer them free without tracking names.

- Legal help on call. Build referral lines to public defenders and specialist teams like the Sex Workers Project (UJC) and local defender offices with vacatur expertise.

- Trauma-informed care. Short waits, warm handoffs, and options (phone, telehealth, in-person). Pay peer navigators for their time.

For Allies and Community Groups

- Support credible orgs. Examples: SWOP-USA (U.S. network), Red Canary Song (migrant massage parlor workers), Decriminalize Sex Work (policy), New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective (peer-led health and rights), Hacking//Hustling (research and digital safety). Donate monthly if you can.

- Testify with receipts. Keep it tight: 2 minutes, 1 lived-impact story, 2 data points (The Lancet on HIV; New Zealand’s refusal power), 1 clear ask (e.g., pass a decrim bill, repeal condoms-as-evidence). Submit written testimony too.

- Change the local rules. Push your city to stop using vice stings as performance metrics. Ask prosecutors to adopt non-prosecution policies for consensual adult sex work and to vacate old convictions.

- Media matters. If you work in comms, ban mugshots and “rescue” language for adults. Center quotes from workers. Use “sex worker,” not “prostitute,” unless it’s someone’s chosen word.

- Mutual aid beats one-offs. Fund hotel nights, storage lockers, prepaid phones, and transit passes. These solve immediate safety barriers fast.

For Platforms and Tech Folks

- Safety features save lives. Studies on indoor and online markets found a ~17% drop in female homicides when screening moved online with Craigslist’s erotic services. Build consented verification, blocklists, in-app check-ins, and quick “panic” exits.

- Don’t over-enforce. Shadowbans and vague nudity rules push people to riskier channels. Write clear adult content rules and allow harm-reduction info.

- Privacy by default. Minimize logs, let users scrub metadata, and offer burner profiles and masked numbers. Support two-factor authentication apps, not just SMS.

For People Doing the Work (Safety, Digital, Health, Legal)

These tips are not a substitute for good policy, but they can lower risk today.

- Screening and check-ins: Keep a simple intake script (name, contact, references, payment method). Set a check-in buddy and a code word for “I need help now.” Share location only with people you trust.

- Payments: Avoid writing explicit notes on payment apps. Expect chargebacks; screenshot receipts. Cash or instant methods reduce chargeback risk but have other trade-offs-choose what fits your risk tolerance.

- Devices and accounts: Use a separate phone or profile for work. Turn on two-factor authentication. Use a password manager. Prefer Signal for sensitive chats. Strip photo metadata before sending (most phones let you share “without location”).

- Bad-date info: If safe, join or create a community “bad date” list. Share only what’s needed (description, contact, behavior, location).

- Space setup: Keep exits clear, lock away personal mail/IDs, and stage a “knock-and-go” plan with a neighbor or friend if that makes sense for you.

- Supplies: Carry condoms, lube, clean towels, a small first-aid kit, and Narcan if you or clients use drugs. Many states let you get naloxone at pharmacies without a personal prescription; most have Good Samaritan protections for calling 911 in an overdose.

- Health: Know where you can get PEP fast (urgent care, ER, some clinics). Ask about daily or on-demand PrEP (2-1-1 dosing is CDC-supported for adult men who have sex with men; ask your clinician what’s right for you). Set a 3-6 month STI testing reminder.

- Police encounters: You can ask, “Am I being detained?” If not, you can leave. You can say, “I don’t consent to a search.” Laws vary, so look up a local rights card through a public defender office.

- Travel: Research local laws. Some places prosecute digital ads or condoms to imply intent. Don’t carry unnecessary work notes across borders.

- Documentation: Keep incident notes (date, time, what happened) in a secure place. This helps if you choose to report or seek a protective order later.

Quick Template: Two-Minute Testimony

- Introduce yourself and your connection to the issue in one line.

- One story in 30 seconds that shows harm from criminalization or benefit from decrim.

- Two facts: “The 2015 Lancet series projects big HIV drops with decrim; New Zealand’s 2003 reform improved refusal and reporting.”

- One ask: “Vote yes on [Bill #] to remove criminal penalties and fund peer-led services.”

Reliable Resources

- SWOP-USA: swopusa.org - chapters, know-your-rights, mutual aid.

- Red Canary Song: redcanarysong.net - migrant worker organizing and resources.

- Decriminalize Sex Work: decriminalizesex.work - policy tracking and bill support.

- New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective: nzpc.org.nz - decrim in practice, health guides.

- Hacking//Hustling: hackinghustling.org - research on FOSTA-SESTA and digital safety.

- Sex Workers Project (UJC): swp.urbanjustice.org - legal services, vacatur help (NYC-focused).

- St. James Infirmary (SF): stjamesinfirmary.org - peer-led clinic model, tools you can copy locally.

- HIV/STD testing locator: gettested.cdc.gov and locator.hiv.gov - free/low-cost clinics near you.

- Amnesty International & WHO/UNAIDS - policy statements supporting decriminalization and rights-based health care.

Pick one action from your lane this week-send testimony, fund a peer program, add PEP to your clinic formulary, or help someone set up 2FA. Small steps compound into real safety.